“Project Natick” is a Microsoft experiment completed in 2020. On 14 September, the company officially announced the positive outcome of a reliability test of its data centres. The challenge of the project was the location of the technology – at the bottom of the ocean. Naturally, it was necessary to put all the devices in a reliable shell and synchronize them in such a way that there would be no need for maintenance afterwards.

Objectives of the experiment

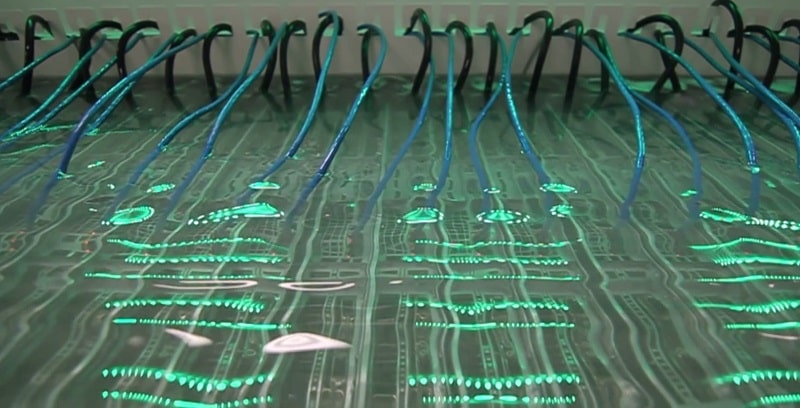

In order to achieve its goals, one of which was to establish a natural cooling cycle, the company used the latest technological solutions. The global ocean temperature makes it possible to eliminate costly ventilation and air-conditioning systems from the server organisation, while the specifics of their functionality require 24/7 continuous operation. The project specialists created a robust capsule that acts as both a protection against water ingress and as a cooling element. This approach to server construction has many advantages:

- territorial placement, which results in shorter distances from network users and minimizes the scanning time of search queries. After all, a study found that 45% of the world’s people live within 100 km of a coastal area.

- there is no need for artificial ventilation and cooling.

- Construction time: up to 3 months instead of several years for a standard data centre.

4 Exclusion of all negative factors inherent in data centres on land – adverse weather conditions, force majeure by maintenance personnel, the impact of atmospheric phenomena, in particular – moisture.

The disadvantages are the lack of standard maintenance, but the risks are minimised by the longevity and uninterrupted functionality of the design.

What is the project?

To prove the right of worldwide distribution of such technology, Microsoft began experimenting in 2015. When a team of experts became convinced that it was possible and there were prospects for the development of server installations on the ocean floor, 864 of the company’s servers were placed in a capsule, appropriately named “Northern Isles”, at a depth of 35 metres in spring 2018 near the Orkney Islands. Over several years, tests were actually carried out, confirming the reliability of this design: there were eight times fewer failures than their land-based counterparts.